Aimee Merrydew (PhD Candidate and Graduate Teaching Assistant in English Literature, Keele University)

Working collaboratively online is different to face-to-face group work in a physical classroom. Students may not know others on the course or how to work as part of an online team. So how do we get students working together and gaining each other’s trust outside of the familiar seminar setting?

This post will focus on strategies to embed community-building activities throughout modules and programmes. Each of the following community-building activities can aid students in building academic relationships, gaining a sense of belonging as historians, and dispelling feelings of isolation when working remotely. Virtual community-building activities have been linked to student success and retention.

1. Weekly virtual coffee mornings

Virtual coffee mornings are a great way to bring students together on a regular basis so they can socialise and relax outside of work. Historians at the University of Lincoln have used virtual coffee mornings as a means of building an online community for Art History and History students in the wake of COVID-19. Dr Michele Vescovi (History, University of Lincoln) explains their rationale for organising weekly coffee mornings:

When teaching was moved online, we decided to create a virtual platform (Coffee@Home), a one-hour weekly virtual meeting for staff and students over a cup of coffee or tea. The purpose was just to have a conversation about our studies, our lives, and what we were doing while in lockdown. Through this, we wanted to maintain the strong sense of community that our students built in the classroom and beyond.

Coffee mornings can take place on various platforms (e.g. Microsoft Teams or Google Hangouts) and students can choose to interact with one another via video-calling or instant messaging.

A virtual coffee morning can be effective for building community within a small unit such as a tutor group, or you might also consider opening the virtual coffee morning to all students in a module, cohort, or programme. In either case, it will help students to build connections that can pave the way for future collaborative learning experiences, as well as helping to socialise the student group in a context in which they won’t have many opportunities to meet in person. Virtual coffee mornings can also help to create a sense of belonging which, in turn, can help to make students feel more comfortable when engaging in more formal group work on and offline.

2. Social annotation

Social annotation is a good way of getting students interacting with one another (and sources!) when working remotely. In this interview, Anna Rich-Abad (History, University of Nottingham) talks about how her students used a tool called Talis Elevate to engage in social annotation and ‘recreate’ the classroom environment.

As we can see from the below image, the tool enables students to annotate primary or secondary sources, respond to other students’ comments, and develop discussions. This activity promotes critical dialogue that may otherwise be ‘lost’ outside of the familiar classroom setting, as students form a community of scholars working together to annotate a source.

Image: Natalie Naik from Talis

Here are some strategies for engaging students in social annotation:

- Begin by getting students to practice using the tool by completing simple tasks, such as adding questions or comments to sections that they found particularly interesting or challenging (or just don’t understand), then ask them to respond to one another’s posts. Dr Jamie Wood (History, University of Lincoln) discusses this strategy here.

- Once students are more familiar with the annotation tool, encourage them to work together to take a short passage from a source and find as many possible meanings depending on what context they are supplied.

- You could also instruct students to identify the social and historical contexts at work in a specific passage. By working from the same document, students can build on each other’s interpretations and engage in knowledge creation.

- Another option is to assign different interpretive strategies, e.g. one group of students reads for ‘Whig History’ interpretations, while another poses as ‘Namierite’ readers. Students can then comment on how closely their peers have mimicked the reading strategies of a different historiographical school.

3. Digital scrapbooking

Digital scrapbooking is great for collaborative working and community-building. Students and educators can co-create a ‘virtual learning wall’ by posting content and comments on online bulletin boards such as Padlet (which can be integrated into the VLE).

This blog post by Professor Lucy Robinson (History, University of Sussex) provides a useful example of how digital scrapbooking might work in practice. Robinson divided her seminar group into sub-teams and instructed them to create their own open access educational resources on a topic of their choice. Each of the groups used Padlet to share and store links and resources; one group also set up Padlet as a public space where users could post comments and feedback on the wall. Padlet was the chosen tool because, as Lucy explains here, it ‘was easy to use, pretty much anything could be added to it, it could be edited by multiple users at once, and had various privacy settings’.

See here and here for more inspiration on digital scrapbooking.

4. Online book club

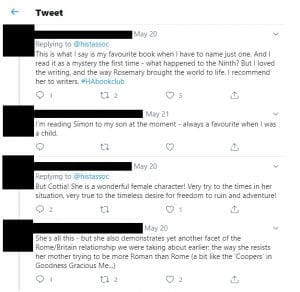

Book clubs are a great way to promote group cohesion and learning outside of the formal classroom setting. The Historical Association (HA) provides an example.

HA Book Club members meet on Twitter and/or Facebook every other Wednesday for an hour to discuss a given text, though the meetings have been expanded during June and July from an hour to a full afternoon. This set-up enables conversations to emerge asynchronously, as people ‘can dip in across the afternoon and evening, leave messages, “like” other people’s thoughts and get caught up in conversations if they wish’. Students can engage in collaborative learning and debate about an assigned book by liking, retweeting, and commenting on each other’s posts, as seen in the screenshot below.

Image: screenshot of @histassoc Twitter thread

To ensure accessibility, you can distribute set readings on a file sharing platform, such as the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) or Google Drive. It goes without saying but it’s important to be mindful of copyright regulations when uploading and distributing material (this is less likely to be an issue if you use services supported by your institution).

Once you’ve shared the material, you can then tweet discussion questions and/or statements for students to respond to and debate as a group. Click here and here for some practical tips and ‘watchouts’ for using Twitter in the virtual classroom.

Alternatively, you can use telecommunication applications (e.g. Microsoft Teams), digital bulletin boards (e.g. Padlet), or annotation software (e.g. Talis Elevate) to facilitate book club discussion. Some services, such as Talis Elevate (see above) and Hypothes.is will allow annotation and discussion directly on resources, which makes it easier for students to engage in conversation about specific moments in the book.

5. Online film club

The book club format can be adapted for a film club. Students can watch films individually and then engage in group discussion and debate. #Covideodrome is one example of an online film club that brings students together on Twitter and Zoom to discuss Netflix films during the lockdown period.

Note: Film clubs provide a fun way to foster collaborative learning through a shared and interactive learning experience, but they may not be accessible to all because they require higher bandwidth technologies in order for films to be watched online (they may also require entertainment subscriptions which can be costly). Note also that all videos should be captioned for accessibility purposes. History UK Fellow Louise Creechan provides useful tips on making videos accessible here.

6. Virtual writing retreats

Virtual writing retreats provide opportunities for community-building and collaborative learning by enabling students to join a community of researchers, share goals for accountability, and progress their writing in a structured and supportive environment. Virtual writing retreats can create a sense of being in ‘this’ process together.

The David Bruce Centre for American Studies uses virtual writing retreats to foster a sense of community and promote collaborative learning amongst historians and humanities researchers. The Centre uses low bandwidth communications software (e.g. Google Hangouts or Slack), which enables more people to participate.

While the David Bruce Centre retreat runs across a full day, shorter time-frames might work better for student groups.

| David Bruce Centre Virtual Writing Retreat

(6.5 hours) |

Shorter Writing Retreat for Student Groups

(90 mins) |

| 09:00 – 09:15: Introduction | 09:00 – 09:05: Introduction |

| 09:15 – 09:30: Planning and goal setting (share with group) | 09:05 – 09:15: Planning and goal setting (share with sub-group) |

| 09:30 – 09:35: Writing warm up | 09:15 – 09:20: Writing warm-up (e.g. freewriting) |

| 09:30 – 11:00: Writing (1 hr 30 mins) | 09:20 – 09:40: Writing (20 mins) |

| 11:00 – 11:20: Break and discussion | 09:40 – 09:50: Reflection and sharing |

| 11:20 – 12:35: Writing (1 hr 15 mins) | 09:50 – 10:10: Writing (20 mins) |

| 12:35 – 12:40: Stretching session for writers | 10:10 – 10:30: Tips on setting goals for how to take work forward

|

| 12:40 – 13:30: Lunch break and discussion | |

| 13:30 – 15:00: Writing (1 hr 30 mins) | |

| 15:00 – 15:05: Stretching session for writers | |

| 15:05 – 15:30: Reflections and feedback on the day |

These schedules encourage students to set writing goals and share them with one another to achieve a common goal: to progress writing projects in a supportive online environment. The regular planning and discussion slots provide opportunities for collaborative learning and community-building, as students can discuss their writing topics and share tips and resources with each other. See here for more tips on organising writing retreats for students.

Get involved and share your experiences

We are keen to hear from you and invite you to join us on Twitter (@history_uk) at 2pm on Thursday 16th July. Here we will invite you to share your experiences, reflections, and resources to help us develop an effective approach to supporting online learning communities in History and the wider Humanities. Use #PandemicPedagogy and/or #SocialLearningHUK.

Aimee tweets at @a_merrydew and blogs (about her research and teaching) at www.aimeemerrydew.com. You can find out more about Aimee’s work on her university profile and personal website.

You must be logged in to post a comment.