Prepared for History UK by Kate Cooper (Royal Holloway/ @kateantiquity), Louise Creechan (Glasgow/ @LouiseCreechan), Lucinda Matthews-Jones (Liverpool John Moores/ @luciejones83), Aimee Merrydew (Keele/ @a_merrydew), Yolana Pringle (Roehampton/ @y_pringle), Manuela Williams (Strathclyde/ @ManuelaAWill), and Jamie Wood (Lincoln/ @MakDigHist).

Download a PDF of the Handbook

In 2020, History departments suddenly had to think seriously about how to move teaching online. For most, this ‘emergency phase’ was a daunting and challenging time, but for some historians, there was also a sense of cautious excitement. As a subject-area, we have tended to prefer physical settings and interactions over digital ones. The Canadian historian Dr Sean Kheraj has observed that COVID-19 is making us use tools that are unfamiliar to many historians and forcing us to upskill to work within a digital landscape that we have often overlooked.

At History UK, we recognised a need to support the history community during this time of transition. From late May 2020, a group of Steering Committee members have been meeting to discuss how to do this. We have run a series of Twitter chats to see what colleagues have learned from the new role online learning has come to play, and have written a series of short posts (on learning design, lectures, contact hours, assessment, accessibility, and community building in the classroom and in wider cohorts) and gathered feedback from the wider community.

Finally, we have produced this short guide to help colleagues in thinking about what it means to move our teaching online. We have framed it around a number of questions:

- What happens to our students’ experience of learning, in and out of the ‘classroom’?

- What happens to accessibility?

- What happens to community?

- What happens to seminars?

- What happens to primary source work?

- What happens to lectures?

- What happens to assessment and feedback?

This is not the end of our commitment to creating a space for collaborative conversations around pedagogy in the time of a global pandemic. Please share your insights via the comments section on this webpage or with @history_uk using #PandemicPedagogy. We are especially interested to hear from you if you have practical examples of approaches to teaching History online. Do pass the Handbook on to colleagues and encourage them to engage with our work. We are also interested in receiving feedback on the Pandemic Pedagogy Handbook itself. Please do let us know if it has informed your practice.

What happens to our students’ experience of learning, in and out of the ‘classroom’?

Download a PDF of this section

Learning was never only about what happens in class, but this is going to be more true than ever. The QAA Guidance on Contact Hours explains that learning activity in the UK is measured in two ways: the ‘level’ of learning in terms of Learning Outcomes, and the ‘amount’ of learning in terms of Notional Study Hours. Each module has an ‘academic credit value’, with10 credits equalling 100 hours of study. So a normal undergraduate year load of 120 credits adds up to 1200 study hours; this makes it roughly equivalent to a 40-hour work week across 30 weeks.

One of the most serious challenges for students will be how to organise their independent study and where to make it happen. Jim Dickinson of Wonkhe, a former director of the National Union of Students, has some sobering and provocative thoughts on this: What exactly are students going to do with their time? and If we must reopen campuses, we mustn’t waste them on teaching.

Squaring the Circle. One solution to this conundrum would seem to be something that many of us in the face-to-face classroom were creating without knowing we were doing so: Presence. But what is Presence? David White, Head of Digital Learning at University of the Arts London, makes a stab at defining it in The need for Presence not ‘Contact Hours’. Creating a sense of being seen and heard and engaged – a sense of shared enterprise with a tutor and, equally importantly, peers to bounce off of – may come instinctively in the face-to-face classroom, but in a virtual environment it requires careful planning and deft implementation.

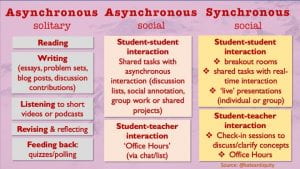

Image: In this chart Kate Cooper looks at the role peer-to-peer and social learning play in learning design (Source: Kate Cooper, Should we stop worrying about contact hours? )

For Staff: We need to shift from thinking about ‘contact hours’ to thinking about what actions offer the best support to learning. Long hours in Zoom meetings are no substitute for the ‘buzz’ of the real-life classroom. What is needed is a sequence of carefully designed prompts, provocations and check-ins that support students by offering guidance and the reassuring sense that they aren’t alone. When benefit to students comes from design and implementation rather than physical presence, this will also have a knock-on effect in how institutions think about staff workload.

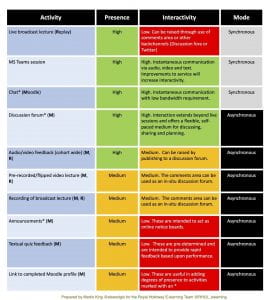

Image: In this chart Martin King shows that asynchronous strategies can achieve ‘presence’. (Source: Martin King, Considerations for online teaching: Presence)

Further Reading:

- Building Community & Presence in Online Learning by Kevin Chamorro, Jon Hoff, Keith Mickelson & Tyler Skillings, from Designing Online Courses: A Primer, distinguishes between teaching presence and teacher-centred presence. They see teachers as most effective when perceived as being ‘present’, but without being the centre of attention.

- On the History UK Blog, read Kate Cooper (Royal Holloway), Should we stop worrying about contact hours?

We would love to hear about your experiences and challenges in relation to the student experience. Please share your thoughts, links, etc. in the comments section below.

What happens to accessibility?

Download a PDF of this section

The transition to remote learning has the potential to exacerbate the accessibility issues experienced by an increasingly diverse HE student population. Disabled students and students from widening participation backgrounds are more likely to be adversely affected by the move of university courses online.

For disabled and vulnerable student groups, remote delivery presents additional challenges to learning as their strategies may not translate to online spaces. Support staff and non-medical helpers may be furloughed or unable to carry out their work with the students remotely. Social distancing means that many students have been separated from their usual support network; vulnerable students and care-givers may be finding this especially challenging. Some students are experiencing the financial strains of lost part-time work, isolation in private accommodation, or living in a difficult environment. Limited access to campus means that some are without a quiet workspace, suitable equipment, and/or a secure internet connection.

Prioritising accessibility at the design stage means that students can gain access without unnecessary delay and complication. (It’s also important to be aware that many students with learning disabilities only receive a diagnosis upon coming to university.) Accessibility strategies often benefit the wider community (including abled and neurotypical students), so the benefits of a proactive approach are far-reaching.

Things to think about

- Asynchronous and manageable chunks. Provide as many opportunities as possible for students to engage in asynchronous learning. This mode of delivery mitigates many access issues that could occur with the shift to remote teaching. Many people report heightened fatigue and concentration difficulties after switching to home-working (Zoom fatigue, for example). Additional screen-time and remote interaction have a cumulative effect; the result is mentally and physically draining. Try to include offline activities in your course planning, add breaks into your synchronous contact time, and find ways to break down materials into manageable chunks.

- Low bandwidth methods. Message boards and fora are a valuable low-bandwidth method of encouraging students to exchange ideas with one another. Be careful about imposing the norms of academic English with respect to spelling, grammar, and register: a casual tone, GIFs, memes, and informality can help under-confident or dyslexic students to feel comfortable engaging in writing that is visible to others.

- Use a variety of formats. Vary the formats of engagement, allowing students to respond to materials through a blend of text, image, audio, and video.

Things to watch out for

- All public sector websites, including HE institutions, will have to conform to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines from September 2020 (note: under the terms of the 2010 Equality Act, we are required to ‘make reasonable adjustments’ to enable all students to access their studies). These regulations ensure that online content is accessible by requiring accommodations such as captioning for videos, making transcripts available, and formatting that supports document readers.

- Use a checklist to ensure that your resources are accessible and support assistive technology. Strategies such as limiting colour schemes to two colours, using 12-point font, or inserting alternative-text descriptions for images, can improve accessibility significantly. The handout 10 Tips for Creating Accessible Content from the Georgia Tech Web Accessibility Group offers a useful overview of inclusive formatting. The Digital Accessibility Checklist from Oakland University is also useful.

- Remote learning can exacerbate barriers related to socioeconomic status or personal circumstances that may have been hidden in the face-to-face classroom. Students may have limited access to quiet workspaces and/or suitable equipment, or unreliable internet connections. Promoting asynchronous learning for low-bandwidth requirements helps students to engage with material whatever their circumstances.

- Always provide transcriptions of audio and video content. This ensures that deaf students, students with limited mobility to take notes, or students without a quiet workspace are not disadvantaged by the mode of delivery. Captioning must also be used for video content. You can find guides to captioning PowerPoint presentations here and YouTube videos here, or on the website for your preferred platform.

Further Reading

- Widening Participation with Lecture Recording Video Playlist – The output from a series of three workshops held as part of a research cluster on lecture capture. Especially useful is the first video which focuses on inclusive remote learning. The second video from the University of Glasgow’s Widening Participation (WP) team outlines the barriers faced by WP groups. The final video, ‘Ten Simple Rules for Supporting an Inclusive Online Pivot’, offers a clear list of guidelines. (Fuller discussion can be found in an OA pre-print here.)

- Teaching in Higher Ed Podcast: Inclusive Practices Through Digital Accessibility – this 30-minute interview with Christina Moore, Virtual Faculty Developer at Oakland University, explores simple habits that can make a significant impact on accessibility.

- Impact of the Pandemic on Disabled Students and Recommended Measures – a report published by Disabled Students UK (@ChangeDisabled) that outlines the concerns that many disabled students have regarding the shift to remote teaching.

- Accessible Teaching in the Time of COVID-19 – this blog post by Aimi Hamraie observes that disabled people have for decades been using technology as a means of navigating higher education, so there is much to learn from listening to their experiences.

- Video paper: ‘On Accessibility’ – Andrea MacRae’s excellent ten-minute flash paper recorded as part of the English Association Shared Futures series explores what accessibility guidelines mean in practice. The paper begins at 0:38:03.

- Media and Materials for Universal Course Design – infographics and links to additional resources make this guide from CAST both comprehensive and easy to navigate.

- QAA Scotland: Enhancing Inclusion and Accessibility Resources Page – a list of resources broken down by medium. Of note is the sharable short video from Jill Mackay (Edinburgh) on the essential considerations for accessible remote course design.

- On the History UK Blog, read Louise Creechan’s Accessibility in Remote Learning – why does it Matter?.

We would love to hear about your experiences and challenges in relation to accessibility. Please share your thoughts, links, etc. in the comments section below.

What happens to community?

Download a PDF of this section

Whether it is a matter of organising online induction activities for first year students or energising a small-scale study group of third-years who have worked together previously, building community is more important than ever. It goes without saying that there are specific challenges when it comes to building online learning communities; what comes naturally in a face-to-face interaction has to be plotted far more intentionally online.

Add to this a raft of factors beyond our control: unequal access to technology and the internet; mental and physical illness (which may have been caused or exacerbated by the global pandemic); unsuitable or unsafe home environments; and competing care and/or work responsibilities. These factors can make it difficult for students – and tutors – to participate in online learning communities.

However, the current disruption also brings opportunities for re-thinking community-building. Moving online can allow for flexibility; this, in turn, may help to widen participation, as students can engage in asynchronous learning activities on their own time and arrange them around competing responsibilities. A move to blended learning also presents opportunities for inclusivity, allowing students for whom travel poses a challenge to access learning communities more freely without needing to travel to physical classroom spaces. Moreover, the ability to engage in online discussion without the pressure of speaking in front of a ‘live’ audience can empower quieter or socially anxious students to join in with shared learning experiences more fully.

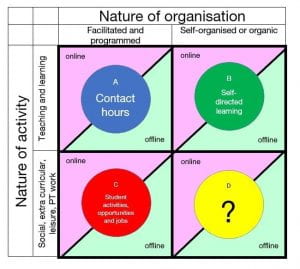

Image: this chart by Jim Dickinson calls attention to the importance of structured and unstructured social engagement – both are crucial to student wellbeing. (Source: Jim Dickinson, What exactly are students going to do with their time?)

Things to think about:

- Embed ongoing community-building activities at module and programme level to aid new and returning students in developing a sense of belonging, reduce feelings of isolation, and enhance student retention.

- Asynchronous activities offer greater flexibility than synchronous ones, making it easier for all students to participate in the learning community. A recent talk by Sophie Nicholls (Teeside), Creating Compassionate Learning Communities Online, explains why asynchronous engagements are so important to inclusive learning communities and offers practical strategies, with links to a range of additional resources.

Things to watch out for:

- Build trust. This is critical to any learning community, but doing so online poses specific challenges. Establish ‘ground rules’ for inclusive communication early on at module and programme level, so students learn how to practice respectful and productive classroom communication when working remotely. It helps to include students in the process of establishing these rules. Tammy Matthews’s 5 Discussion Ground Rules for the Online Classroom and this post on Establishing Ground Rules from Cornell’s Center for Teaching Innovation offer tips on how to create a consensus around ‘ground rules’.

- Be generous with opportunities to connect, but sparing in unnecessary demands. Some students will be facing difficult circumstances that may or may not be related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Including community-building activities throughout a programme or module can help to foster a sense of belonging, but try not to create pressure for students to engage in too much activity that is synchronous when it could just as easily be asynchronous – this can add to already existing stresses. Anthea Papadopoulou’s How to Build an Online Learning Community (2020) offers useful suggestions.

- Remember, students may be wrestling with complicated personal situations and limited internet access – see the Access section of this Handbook for suggestions.

Further Reading:

- Building an online community from the University of Sheffield’s Elevate team offers clear-eyed thinking on how to anticipate problems by thinking ahead, and practical solutions to address them. It includes a useful section on peer-led activities, which are crucial for empowering students in the learning process and are often overlooked in the transition to digital learning.

- Humanizing Online Teaching, a paper by Mary Raygoza, Raina León and Aaminah Norris (all from Saint Mary’s College of California) provides really helpful guidelines based around the notion of ‘Beloved Community’. What makes this paper so useful is its range and comprehensiveness, with attention to a wide variety of pedagogical practices.

- Read Aimée Merrydew’s Building Online Learning Communities post on the History UK blog for a list of suggested community-building strategies.

We would love to hear about your experiences and challenges in relation to community. Please share your thoughts, links, etc. in the comments section below.

What happens to seminars?

Download a PDF of this section

Seminars, and more generally small group discussion and activities, are a well-established and effective way to promote interactive learning, offering students a chance to take ownership of their learning processes and to explore ideas with their peers. For some, the relationships forged during the first week of class will translate into long-term friendships and support networks.

So in thinking about how to re-invent the seminar for the online pivot, we need to think about building online learning communities. Students are likely to be concerned about losing immediate and personal contact – with one another and with their tutor. As Simon Usherwood (University of Surrey) puts it, there is a danger that ‘the soft stuff that happens around your classes – the checking-in, the responsiveness – drops away’.

But there is also much to cherish in the opportunity to explore what makes great teaching in a new and relatively untested environment. By setting out a variety of flexible activities that are self-paced and encourage students to become more aware of how they learn as well as what they learn, we will almost certainly find new ways to engage with our students. For example, we can engage them in co-creating ‘lesson’ plans and activities, re-designing seminars with and not merely for our students. After all, encouraging students to be co-creators and co-learners can only benefit the learning process, whether it takes place online or on campus.

Things to think about:

- The key thing to focus on is interaction. Student-Centered Remote Teaching: Lessons Learned from Online Education by Shannon Riggs (Oregon State University) invites teaching staff to consider three main interactions at the heart of the online environment: student-content interaction, student-student interaction and student-tutor interaction.

- Create chains of consequence. Ensure that the focus is not just on a specific ‘session’, but that there are activities preceding and following it that link to the wider learning architecture of the module, and toward the learning objectives the students are aiming for. Gilly Salmon’s Five Stage Model offers an insightful approach to structuring what she calls ‘e-tivities’.

- Focus on teaching, not the technology. The design of the module and the engagements and activities that take place within it matter more than the technology used. Sophisticated technology will not improve poorly planned and delivered teaching, just as modest technology can adequately support good teaching. (This infographic from Sophie Nicholls, Low-Tech Online Learning Activities, offers a reminder that a mix of activities that keeps the focus on interaction does not have to be high-tech.)

Things to watch out for:

- Clear communication from the beginning is very important – make sure students understand seminar structure, resources, activities and especially expectations of participation and engagement.

- Accessibility is more important than ever, so it is important to find a careful balance between the provision of asynchronous and synchronous content. Asynchronous strategies encourage students to manage their own learning process, and are often more effective than synchronous ones. They also draw in participation from students who might hang back in a videoconference or face-to-face setting.

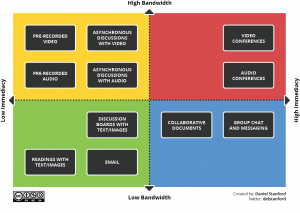

- Consider Bandwidth. Keep videoconferencing to a minimum. Not all students will be able to participate in regular hour-long Zoom seminars, whether because of bandwidth issues, personal circumstances, or Zoom fatigue (which can become aggravated for both staff and students when multiple modules require multiple sessions). Be sure to use alternatives to videoconferencing where possible. When the benefits of videoconferencing outweigh the bandwidth cost, see the following tips by Doug Parkin.

Image: Daniel Stanford’s chart shows low & high-bandwidth tools (Source: Daniel Stanford, Videoconferencing Alternatives: How Low Bandwidth Will Save Us All)

Further Reading:

- Fostering Student Participation in Remote Learning Environments A short guide from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, which focuses on ways to establish opportunities for interactivity and social engagement, and to keep feelings of isolation or exclusion at bay.

- Designing learning and teaching online: the role of discussion forums Useful tips on teaching practices in a remote learning environment, with advice on how to design online activities (which can be built into synchronous seminars or conducted asynchronously).

- QAA UK’s Questions to Inform a Toolkit for Enhancing Quality in a Digital Environment offers in-depth guidance; section 3 on student-centred teaching, learning and assessment is particularly useful.

- On the History UK Blog, read Aimée Merrydew’s Building Online Learning Communities.

We would love to hear about your experiences and challenges in relation to seminars. Please share your thoughts, links, etc. in the comments section below.

What happens to primary source work?

Download a PDF of this section

Primary source work is at the heart of what historians do. Yet creating learning opportunities for this core skill presents a challenge, especially in the online classroom. Facilitating discussion boards that come ‘alive’ and ignite students’ curiosity requires special skills. However, despite these challenges, moving primary source work online opens up opportunities to disrupt one-way knowledge transfer, to focus on skills development, and to include a wider range of student voices in discussion.

A wide array of techniques and platforms is available to support collaborative reading, such as social annotation tools (e.g. Hypothes.is, Perusall, and Talis Elevate) and virtual bulletin boards (such as Padlet), each of which has its own benefits and limitations. Both approaches allow students to curate their own collections of online material. When effectively facilitated, digital strategies for collaborative reading can help develop critical awareness of source quality and context, alongside students’ digital literacy.

Embedding collaborative work with pre-selected documents and images into weekly activities can make online spaces more dynamic. Rather than simply asking students to ‘read’ the sources (which can encourage a surface approach to the material), requiring them to add comments, questions, and highlights to primary sources can deepen learning by encouraging students toward active engagement with what they have read.

Things to think about:

- There are both synchronous and asynchronous ways to set the stage for collaborative primary source work. This can be achieved through a discussion board or virtual seminar, particularly if you can break students into small groups. Dedicated platforms such as Talis Elevate, is, and Perusall allow students to mark-up text and images, and provide opportunities for students to add their own material. Adam Sheard (University of British Columbia) offers a great comparison of some of the major platforms, Which Collaborative Annotation App Should I Use?

- Each approach to primary source work offers different levels of student engagement, openness of inquiry, and analytical depth. Take advantage of the chance to encourage new forms of engagement with primary source material. In Back to School with Annotation: 10 Ways to Annotate with Students Jeremy Dean explores annotation strategies using Hypothes. In this micro-site for the Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities project, Paul Schacht (State University of New York) brings together examples showcasing the possibilities of annotation. This post on Padlet Maps and Timelines by Anne Hole of the University of Sussex looks at using Padlet to allow students to pool the evidence they have gathered. The Introduction to Perusall by one of its developers, Gary King (Harvard), discusses the cognitive profile of social annotation as a framework for learning.

- Moving primary source work online requires us to rethink our role in the classroom. Don’t forget that students need to be guided through the process of taking ownership over primary source work.

- Consider encouraging students to take ownership by allowing them to add their own documents, while your role moves from centre stage to monitoring discussions, validating responses, and being prepared to intervene. Jamie Wood (Lincoln) outlines the way he structured his approach to student-led curation of reading materials in the appendix to his article, Helping Students to Become Disciplinary Researchers.

Things to watch out for:

- You will need to guide students through new technology and set clear expectations of what is required. If you ask students to use an unfamiliar platform, explain what value it adds, address any concerns over privacy, and make sure they are able to use it successfully. Test your instructions from a student perspective ahead of time (preferably several times). Dan Allosso (Bemadji State University) offers a good example of introducing social annotation to students in his YouTube is Intro.

- Wherever possible, use platforms that are already widely in use in your institution. This means students are not overwhelmed by managing too many new platforms, and adds to the level of support they – and you – can access. On the American Historical Association YouTube channel, Steven Mintz (University of Texas at Austin)’s Engaging Students Online offers a useful reminder that the choice of platform is less important than making good use of it. Similar results may be achieved through different tools: a Google Doc, a class wiki, or a class blog.

- Online platforms are still the classroom. Consider the impact of these activities on all students, particularly those from marginalised groups who may not feel comfortable or safe interacting online. Even when platforms offer anonymity, inequities can shape practises of commenting, highlighting, and discussion.

- Don’t forget about privacy, data and university copyright policies. Creating a free account with a platform often means giving up certain rights over data and this may have implications for whether it’s appropriate to use it; you will need to start a discussion with your IT department. You may also need to consider copyright – work closely with your library to secure clearance. One solution may be to use primary source material that is openly available online.

Further Reading:

- Lisa Lane (MiraCosta College) explores practical examples on her blog and provides a quick demonstration of Perusall in the video Read and Discuss with Perusall.

- Melodee Beal’s YouTube channel, Clio Digital Workshop, includes discussion of named entity recognition – identifying key people, places, and concepts in a historical source.

- It’s worth browsing Adam Sheard (University of British Columbia)’s YouTube Channel Ed Tech with Adam for tutorials on some of the main collaborative annotation platforms.

- In Passing 1000 Talis Elevate comments Jamie Wood (Lincoln) talks about getting students to take control. (He surveys how others at Lincoln use Elevate here.)

- In An academic’s experience of using Talis Elevate before and after the shift to online, Anna Rich-Abad (Nottingham) talks about using Elevate to ‘recreate’ the classroom.

- Monica Brown and Benjamin Croft’s Social Annotation and an Inclusive Praxis for Open Pedagogy in the College Classroom offers a more in-depth discussion.

We would love to hear about your experiences and challenges in relation to primary sources. Please share your thoughts, links, etc. in the comments section below.

What happens to lectures?

Download a PDF of this section

The lecturer standing in front of a room full of students imparting knowledge is a dominant cultural image of university education, but the centrality of lectures to the teaching and learning process has been challenged since the post-war period. It has long been accepted that it is independent learning, rather than listening and note-taking, that offers the most effective route of access to subject knowledge for most students.

Moving online has the potential to allow us to address some of these concerns. We need to make sure that the lecture-derived content that we create is orientated to sign-posting and scaffolding our students’ independent learning.

The most useful place to begin re-thinking scaffolding is Graham Gibbs, Twenty terrible reasons for lecturing (SCED Occasional Paper No. 8, Birmingham, 1981). In this classic 1981 reflection Gibbs dispels the myths around lectures and note-taking, and makes suggestions for how to reach our students that are still fresh nearly 40 years later.

Things to think about:

- Scaffolding and Signposting. To help students pace their learning, divide material into small, manageable chunks. Make sure that you offer downloadable class materials such as non-recorded PowerPoints and handouts. You will need to communicate with students about how the different materials you have made available tie in with each other and how they should engage with them. You will need to create weekly deadlines that help students know when they should engage with what.

- Monotonous recordings can lead to disengaged students. Think about how to build interaction with your material: pose questions and offer prompts, or ask students to reflect on a theme. Consider variety. Scaffold learning through written blurbs and short video recordings, further engaging students through quizzes, discussion threads, reading tasks, primary source activities or journaling. Alternatively, think about how to represent your individual presence; don’t just be an anonymous voice overlaid on a PowerPoint. Try embedding videos in the PowerPoint recording in a way that allows students to see you speaking alongside your slides.

- Be human. Think about how you communicate with your students, beginning with narration and tone. Then make sure you have a clear and engaging hook into the lecture. You might ease students in by setting up the topic informally, saying hello, offering a titbit of less formal material. This doesn’t have to be pre-recorded; if you are doing it live, you can talk about events from the week or even discuss the weather, sport or television programmes. You might try using social media – a great example by Roxanne Panchasi of Simon Fraser University can be found on Twitter through the hashtag #hist417. Or try different formats: a podcast discussion with a colleague teaching on the module or a fellow academic allow for a more spontaneous feeling.

- It is hard not to strive for perfection, but remember, we are not making documentaries. Be natural. You do not need to let go of the ‘ums’ and pauses. They show our students we are human and help create presence.

- Delivery of recorded material. Audio is more important than visuals. If you are recording lecture material, try to get access to a good microphone. You can record audio to accompany PowerPoint presentations and export them as a video file. Other tools include: Panoptical, Screencast-O-Matic, and OBS.

Things to watch out for:

- The move online makes it all the more important that lecture material is accessible. To comply with current accessibility legislation, all lecture material must be captioned and/or have a transcript available. This also allows students to feel more confident about specialist terms, names and pronunciations. YouTube and Panopto can do this for you, though other captioning software is available, and you will need to leave time to check for accuracy. The University of Washington has a useful guide for thinking about transcription. Kristopher Lovell (Coventry University) has made a video on how to caption video lectures using either free software (Handbrake) or Adobe. More generally, a useful guide to accessibility (in Microsoft) can be found here.

- Avoid streaming lectures. Pre-recording not only allows for accurate captioning, but helps students with poor internet connections. Remember too that students may have legitimate reasons for not attending synchronous lectures. Instead, reserve synchronous slots for reciprocal and interactive sessions and post recorded materials online. Also, videos are often large files and take time to download; Panopto and YouTube offer the possibility of file compression. Ask yourself: does this content need to be delivered in an oral format? Written blurbs could be equally if not more effective.

- Video content should not be 50 minutes long. While conventional wisdom has it that attention wanders after 15 minutes, recent research suggests that the first ‘dip’ in fact takes place beginning at 4 mins 30 seconds. The good news is that short ‘bites’ of content on well-defined sub-topics will allow students to access material in the way that best supports their independent reading.

Further Reading:

- Seven Deadly Sins of Online Course Design. In this classic blog post from 2014, Daniel Stanford (DePaul University) walks through the pitfalls of creating a lively and engaging virtual classroom.

- Lecture Recording. What makes this page from QAA Scotland so useful is the range of resources to assist you with lecture recordings, from practical advice to legal considerations you need to make when producing recorded content. Please note that this is from Scotland, so slightly different accessibility legislation may be in place in England, Northern Ireland and Wales.

- Using Video in Learning and Teaching. Sophie Nicholls (Teeside University) has been designing and using digital platforms for 20 years. This page from her website offers practical advice, including infographics like ‘How to Make Engaging Video for Learning and Teaching’

- Widening Participation with Lecture Recording. This page from the Enhancement Themes programme run by the Scottish Universities looks at how recorded lectures help can support inclusive teaching and learning.

- Historian of Science James Sumner at Manchester has created a series of useful YouTube videos on practicalities. His first video offers tips and advice on how to set up for home recording, while others explain how to use Open Broadcasting Software (OBS) technology to gain greater control of what appears on your screen.

- On the History UK Blog, read Kate Cooper’s Thinking about teaching at a time of uncertainty and Louise Creechan’s But, what about lectures?

We would love to hear about your experiences and challenges in relation to the student experience. Please share your thoughts, links, etc. in the comments section below.

What happens to assessment and feedback?

Download a PDF of this section

Ideally, assessment and feedback can motivate students and help them to focus their learning, but when ‘getting good marks’ becomes the focus, it diverts students’ attention from the essentials. Because of this, re-thinking assessment and feedback as teaching shifts online can potentially benefit our students.

Traditionally, essays and exams have been central to assessment in History. Most students now submit their essays online and e-resources are ubiquitous. Exams can be conducted online, and open-book, time-constrained online assignments offer a viable alternative. On one level, then, shifting assessments online is straightforward. Yet the digital pivot offers an opportunity that should not be wasted, to bring assessment and feedback into a more productive relationship with the learning process.

It has long been acknowledged that exams often encourage a surface approach to learning (Gibbs and Simpson, 2004) and can privilege certain kinds of learners (and demographic groups) over others (Furnham et al., 2008). Such inequities may well be perpetuated or even intensified when moved online. But shifting assessment online opens up opportunities to engage different kinds of learners in new and varied ways, while continuing to develop key disciplinary capacities and career-relevant skills.

Online assessments that are designed to encourage students to engage actively with the digital world may be particularly apt for focusing students’ energies on core areas of historical practice. For example, assessing online research in a structured manner strengthens students’ capabilities in searching for, evaluating and making use of information online. Writing and presentation skills can be built into tasks such as blogging, developing websites and/or making videos or podcasts. Opportunities to practice writing in different registers and for audiences beyond the tutor and immediate peer group can be both exciting and valuable.

Online assessment opens up many possibilities for innovation, including:

- Equity through continuous assessment. E-learning tools enable tutors to evaluate students’ ongoing engagement with a module or topic rather than just their performance in assignments or in face-to-face classes, both of which tend to favour certain demographics over others.

- New skills. Online tasks can be designed to develop valuable skills that are not normally foregrounded in learning outcomes in History courses, such as creativity.

- Alternative assessments. Digital environments may create opportunities to introduce alternative forms of assessment, such as reflective writing in online learning journals.

Given that our professional lives are increasingly digital, setting students predominantly analogue forms of assessment (even if done online) is a mistake. However, whether deployed to support traditional or innovative approaches, it is clear that the shift to online assessment can prepare students very effectively for academic and for the world of work.

Things to think about

- Assessment for learning, not assessment of Setting assessment tasks, conducting assessment and giving feedback (whether formally or informally) offers one of our best chances to help our students prioritise their learning, so think about assessment as a prognostic rather than a diagnostic process. Consider how the overall assessment regime of your course is contributing to the message you are sending to students about what is important. If any element is simply allowing you to measure what they have attained, then remove or reconfigure it. (S. Brown [2005], Assessment for learning, Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1, and D. Wiliam [2011], What is assessment for learning?, Studies in Educational Evaluation 37.1, are useful here.)

- Constructive alignment is key. Assessment is most useful to students when it is aligned with the other elements of your course, especially your learning objectives and the activities students are expected to undertake. (See J. Biggs [2003], Aligning teaching for constructing learning [Advance HE], and Jamie Wood [Lincoln]’s Pandemic Pedagogy – Redesigning for online teaching, or Why learning objectives aren’t a waste of time, which explores the connection between what you want students to learn and how assessment strategies encourage them to direct their energies.)

- Formative assessment makes the process come alive. Build in opportunities for students to get feedback from you and their peers, and to reflect on their own performance, across the module. This doesn’t have to be a ‘draft essay’; it can simply be informal ‘checking-in’ points. (See Z. Baleni [2015], Online formative assessment in higher education: Its pros and cons, Electronic Journal of e-Learning4.)

Things to watch out for:

- It may take a long time for formal changes to assessment to be approved by your institution; factor this into your planning, but also think about trying things out informally and talking to your students about your plans – they can be valuable allies.

- Students may experience issues accessing and engaging with online assessments, especially if they are time-constrained and dependent on a reliable internet connection. Staff face some of the same issues: remember that marking on screen can be challenging for some; see Sandra Rankin and James Demetre, The Experience of Online Marking and the Future Development of Online Marking Practice.

- There is a strongly-held view in parts of the academy that essays and exams are the ‘gold standards’ of assessment. Here, rather than engaging in arguments with colleagues about the merits or otherwise of essays/ exams, it is useful to show how innovative forms of online assessment enable students to meet learning outcomes. ‘Traditional’ and innovative, digital forms of assessment can coexist.

Further Reading

- Getting your teaching online – Advice from QAA Scotland including a number of helpful links in the ‘assessment’ section.

- New Ways of Giving Feedback – Overview of innovative feedback strategies from the University of Edinburgh, with links to a wide range of case studies and publications.

- Ungrading – a call for a radical overhaul of approaches to assessment, from Jesse Stommel (including how-to advice).

- Assessment Strategies – Fantastically useful module on strategies for assessment from Queens University, Canada; work through it at your own pace.

- How COVID-19 has changed student assessment for good – A story about the ‘future of assessment’ from JISC, drawing on a report released in 2020 and studies of approaches taken during lockdown.

- Beyond essays and exams: changing the rules of the assessment game – This blog post from Jamie Wood (University of Lincoln) considers how online assessment can support deeper student learning, with a number of links to case studies.

We would love to hear about your experiences and challenges in relation to assessment. Please share your thoughts, links, etc. in the comments section below.

You must be logged in to post a comment.