The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to affect the ways in which history is taught and assessed at universities. Following on from our Pandemic Pedagogy Handbook, History UK has commissioned a series of blog posts exploring how staff, students and institutions have responded to this continually evolving situation and the pedagogical challenges it has presented.

The first post in this series is by Amy Louise Blaney, a PhD student at Keele University. Her thesis examines the afterlife of the Arthurian legend in the long eighteenth-century and its intersection with national identity formation. Amy is also a part-time lecturer in English at Staffordshire University, as well as a co-editor for Keele’s Under Construction postgraduate journal.

Covid-19 required rapid adaptations of teaching pedagogy and practice and it has been heartening to see HE teachers and lecturers engaging in innovative, accessible, and original teaching in these challenging environments.

Recreating informal and social spaces has, however, proved more difficult. As a student, I have missed the informal conversations that take place with both my peers and my lecturers – the chance encounters over coffee, or the chats that occur before and after lectures and seminars. And as a tutor, I’ve found re-creating such spaces online particularly challenging.

My first online teaching session felt sorely lacking in informality. Launching straight in seemed to leave students cold despite my attempts to create a cheery atmosphere. Getting them to talk to each other – let alone me – felt like trying to cross a digital wilderness, bereft of the friendly gestures that help in situ teaching sessions to get off the ground. We got there eventually, but I came out of it feeling that there was something lacking.

I mentioned this in passing to my mum – a Quality Improvement Officer for the NHS – and she suggested taking 5/10 minutes to ‘warm up’ my crowd. Warm-up activities had worked well with the adult learners on her training courses and, she said, had helped increase engagement.

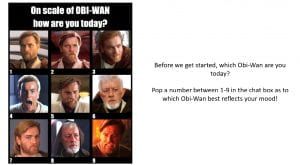

Given that anything is better than talking into a void, I decided to give it a go and re-arranged my next session to allow for 10 minutes ‘warm-up’. Deciding that even if I couldn’t get students to engage, I could attempt to raise a smile, I raided the archive of internet memes and decided to ask how they felt on a scale of 1 – Obi-Wan.

I’ll be honest, when I got to the relevant slide and asked the question, I was expecting radio silence. Instead, I got a chorus of chat messages with students responding with a number, then replying in chat or via voice if I asked them for a little more detail about how they were feeling. It wasn’t in any way related to the course content, but it woke everyone (myself included) up, got them mentally into the room, and got them talking to both me and to each other.

Since then, my group have told each other how we feel on a scale of cat, made a Mentimeter word cloud about Shakespeare, and played ‘guess the seventeenth-century poet’ together. Students would start chatting as soon as they logged in, asking each other how they were, and responding when I asked them how they’d found the reading and preparation. Sessions were more engaged and livelier. It felt like being in a classroom.

Our activities were only indirectly related to the course content but creating space for such informal conversations is, I feel, vital to learning. As well as providing a sense of comradery and shared experience, conversations that take place within informal learning spaces can inspire new directions in thinking and research and allow for the sharing of ideas and worries in a safe and collegiate space. And if Covid-19 has taught us anything, it is that we need those connections more than ever.

If you would like to contribute a short blog post or podcast/video that addresses how the pandemic has changed or affected history teaching and learning in Higher Education then please email Dr Sarah Holland (sarah.holland@nottingham.ac.uk), History UK’s Education Officer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.