Aimee Merrydew (PhD Candidate and Graduate Teaching Assistant in English Literature, Keele University)

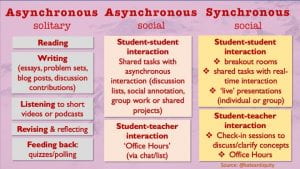

Creating a sense of community for students is an integral part of the learning experience; it helps students to gain a sense of belonging and is linked to student success and retention. But building communities requires building relationships. How can this happen when the opportunity for students to socialise in person is limited due to COVID-19 precautions?

Community-building is especially important for new starters, since the transition to university life can be a challenging process and many students do not know anyone on their course. And it continues to be important across the degree, to tutor groups and departmental cohorts, as well as in a classroom setting. How can students meet fellow historians and gain a sense of belonging when studying online?

This post will focus on strategies that help students to gain a sense of belonging, build their identities as historians, and manage feelings of isolation when working remotely.

Buddying:

For new students, one of the best strategies is a buddying scheme. Keele University’s Student Support Buddies scheme provides a useful example. Keele Student Support Buddies are trained to provide friendly and informal support and guidance to incoming students via email and other forms of communication (e.g. Microsoft Teams and/or social media).

Peer mentoring relationships usually begin pre-arrival and continue throughout the academic year, providing ample opportunity for new and returning students to forge connections with fellow historians. What is particularly useful about ‘buddying’ from a community-building perspective is that it encourages links across year groups, in the process enhancing the community of students studying History.

Additionally, you can share this Historical Association resource with incoming students to support their transition to study history at university.

Virtual coffee mornings:

Virtual coffee mornings provide opportunities for community-building by enabling students to socialise with one another in a relaxed and low-pressure online environment.

Community-building is at the heart of Coffee@Home, a one-hour virtual coffee meeting organised for academic and student historians at the University of Lincoln (though you could also have a student-only coffee morning). The purpose of Coffee@Home was, as Dr Michele Vescovi (History, University of Lincoln) explains, ‘to have a conversation about our studies, our lives, and what we were doing while in lockdown. Through this, we wanted to maintain the strong sense of community that our students built in the classroom and beyond’.

Virtual coffee mornings are relatively easy to set up and can take place on various platforms such as Google Hangouts or Microsoft Teams. These platforms provide students with the option of choosing their preferred method of interaction (e.g. by video-calling or instant messaging).

You could host a virtual coffee morning as part of the induction week and continue running it throughout the academic year. You could even open the coffee mornings to all History students, as this would enable students to make connections across cohorts. In either case, virtual coffee mornings would provide students with a space to meet fellow historians and feel part of a community.

Image from Freepic

‘Ice-breaker’ activities for tutor groups:

Learning is often a social experience, so it’s important that students feel comfortable learning together. But creating shared experiences and supporting memorable connections between students can be challenging in an online environment.

Ice-breaker activities can aid students in getting to know one another when working remotely. Some activities you could try include:

- Show and tell – Ask students to share their favourite historical photo or quotation and explain why they think it’s interesting.

- Who am I? – Students must try to figure out which historical person they are by asking ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions to gain clues about the name assigned to them (you could circulate names in advance of the game).

- Pictionary – Ask students to draw and then circulate pictures about what they like to do, a recent event in which they partook, and/or their reasons for enrolling on the course. Other students can then guess what each student drew, in the process getting to know a little more about each other.

- Medieval personality test – Students can take the test and then share their results with the rest of the group. Provide students with the opportunity to compare and agree or disagree with their results in discussion with one another, as this will get them speaking to each other and identifying any common interests (or differences).

Each of these activities can be conducted over email, on a Google Doc, on a digital bulletin board (such as Padlet), and other types of communications software (e.g. Microsoft Teams, Google Hangouts, and Zoom).

See here and here for more inspiration on virtual ice-breaker activities.

Historical role-playing exercises:

Historical role-playing is a fun way to create an interactive community of learners. The ‘Our Mutual Friends Tweets’ project is one example of a role-playing community that took place digitally. Each month, participants would read the latest instalment of Dickens’ novel and then take to Twitter to record the latest plot developments from the perspective of one of the characters. To add to the fun and community spirit of the project, participants were also encouraged to ‘air their responses to the unfolding plot, as well as responding to the other characters’ tweets’ (Curry & Winyard 2016, 568).

Image: Screenshot of @OMG_Rogue’s tweet

This activity would work well for History students across all levels of study. Students could assume the roles of historical figures and stage debates on issues from a given period. Or they could rewrite history by considering historical events from multiple points of view.

Participants can role-play on Twitter, as was the case in the ‘Our Mutual Friend Tweets’ project, or they can use online bulletin boards such as Padlet (which can be integrated into the Virtual Learning Environment). See this blog post by Dr Lucinda Matthews-Jones (History, Liverpool John Moores University) for another excellent example of community-building through online historical role-playing.

Note that while historical role-playing offers an exciting opportunity to bring students together, it is important to establish ‘ground rules’ for respectful participation, especially when topics are of a sensitive nature.

Virtual escape rooms:

Virtual escape rooms have become something of a phenomenon in recent years. They are fun and educational team-building exercises that encourage players to work together online to complete tasks across a series of locked rooms. Students need passwords to ‘unlock’ these rooms, which they can gain by working collaboratively to solve puzzles, retrieve clues, and gather other information found throughout the game.

Virtual escape rooms can be designed around historical themes. For example, in a Cold War themed escape room, you might have one room titled ‘Secret Bunker’, another titled ‘Space Station’, and so on. To add to the fun and create friendly competition, you could develop two opposing escape rooms: one for the Soviet Union team and one for the United States. Whichever team ‘escapes’ their virtual room first wins the war, so to speak. Escape rooms are usually against the clock, so you can always add a link to this YouTube clock for added pressure.

Virtual escape rooms can take place on various platforms, including Microsoft OneNote, Google Forms, and Classtime. Click here for some ideas about the kinds of history-themed activities you can include in your virtual escape room. Click here for a step-by-step guide on how to make your virtual escape room (using Google Forms).

For more info on supporting online learning communities see this History UK blog post by Aimee Merrydew and this infographic by Dr Sophie Nicholls.

Get involved and share your experiences

We are delighted to invite you to join us on Twitter (@history_uk) at 2pm on Thursday 16th July, where we will invite you to share your thoughts and experiences of supporting online learning communities in History and the wider Humanities. Use #PandemicPedagogy and/or #SocialLearningHUK.

Aimee tweets at @a_merrydew and blogs (about her research and teaching) at www.aimeemerrydew.com. You can find out more about Aimee’s work here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.